The Teachings of Mutton: A Coast Salish Wooly Dog

— Harbour Publishing in Canada

— Distributed by Ingrams in USA Bookshop.org

— In the UK Waterstones or Amazon.uk

The pelt of a dog named “Mutton” languished in a drawer at the Smithsonian for 150 years until it was discovered, almost accidentally, by an amateur archivist. This book tells Mutton’s story and explores what it can teach us about Coast Salish Woolly Dogs and their cultural significance.

Until now, there has been very little written about the enigmatic Coast Salish Woolly Dog, or sqʷəmey̓ in the Hul’q’umi’num language. According to Indigenous Oral Histories of the Pacific Northwest, this small dog was bred for thousands of years for its woolly fibres, which were woven into traditional blankets, robes and regalia. Although the dogs were carefully protected by Coast Salish peoples, by the 1900s, the Woolly Dog had become so rare it is now considered extinct.

Co-authored with weavers, Knowledge Keepers, and Elders, The Teachings of Mutton interweaves perspectives from Musqueam, Squamish, Stó:lō, Suquamish, Cowichan, Katzie, Snuneymuxw, and Skokomish cultures with narratives of science, post-contact history, and the lasting and devastating impacts of colonization. Binding it all together is Mutton’s story—a tale of research, reawakening, and resurgence.

The history of Coast Salish “woolly dogs” revealed by ancient genomics and Indigenous Knowledge – Paper

Ancestral Coast Salish societies in the Pacific Northwest kept long-haired “woolly dogs” that were bred and cared for over millennia. However, the dog wool–weaving tradition declined during the 19th century, and the population was lost. In this study, we analyzed genomic and isotopic data from a preserved woolly dog pelt from “Mutton,” collected in 1859. Mutton is the only known example of an Indigenous North American dog with dominant precolonial ancestry postdating the onset of settler colonialism. We identified candidate genetic variants potentially linked with their distinct woolly phenotype. We integrated these data with interviews from Coast Salish Elders, Knowledge Keepers, and weavers about shared traditional knowledge and memories surrounding woolly dogs, their importance within Coast Salish societies, and how colonial policies led directly to their disappearance.

Read the article at Science

Knowledge Within: Treasures of the Northwest Coast – Book review

A good book should leave something behind in your mind, little nuggets of treasure — a thought to ponder, a quote to repeat, an ending that will not end, a scene you see again and again, a relationship that deepens, a new insight to see with, an image that says so much. Knowledge Within: Treasures of the Northwest Coast leaves you with a selection of these gems.

It is an unusual book. The overarching concept is a book whose chapters each represent a museum or art gallery whose holdings include Indigenous “works of art.” Each chapter is written by someone very familiar with the organization — a current or past staff member. While the concept of Northwest Coast First Nations material ties each chapter together, each chapter is unique and presents different offerings: a history of an institution, collection or of a people; the philosophical basis the organization is built on; an overview of important holdings or exhibits; or, an intention — to make things right.

Read on at The BCReview here

The Salish spinner – innovation, evolution, and adaptation

One of my favorite spinning wheels is a bit of an ugly duckling—it looks a little strange as if it is missing parts: it’s a bobbin and flyer without the wheel, a head without a body—yet when properly assembled on top of an old treadle sewing machine it transforms into a swan complete with a heartbeat and the treadle beats in time with mine. It relaxes and calms me in a meditative way.

It is known by different names: originally the “Indian Head”, the “Cowichan” and now, the “Salish” spinner. It even has brothers and sisters who are complete units with the treadle and the head combined, like the Ashford (a New Zealand company thousands of miles away) Country Spinner. How did this all come to be? The use of the original— ‘Salish’—spinner was unique to the Pacific Northwest, the traditional Coast Salish territory (see map).

Digital copies available here: SpinOff magazine Fall/winter 2022

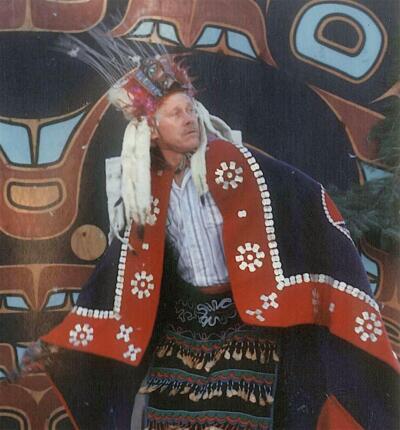

Dempsey Bob In His Own Voice – Book review

It was a pleasure to review this book for the British Columbia Review (formerly the Ormsby Review). The book was written to accompany the exhibit ‘Wolves: The Art of Dempsey Bob‘ . After reading the book and viewing the incredible photographs of the carvings I was compelled to pack my bags and head to Whistler with the quest to view the exhibit up close. The carvings were THAT powerfull. It was magnificent. We viewed it twice, the second time as part of a exquisite dinner by the Alta Bistro and a personal tour package. Head over to the BCReview to read the review and to discover more reviews.

Bill Holm (1925-2020)

An obituary and tribute and a review of books written by, influenced by, or about Bill Holm. Published on The British Columbia Review (which used to be named the Ormsby Review).

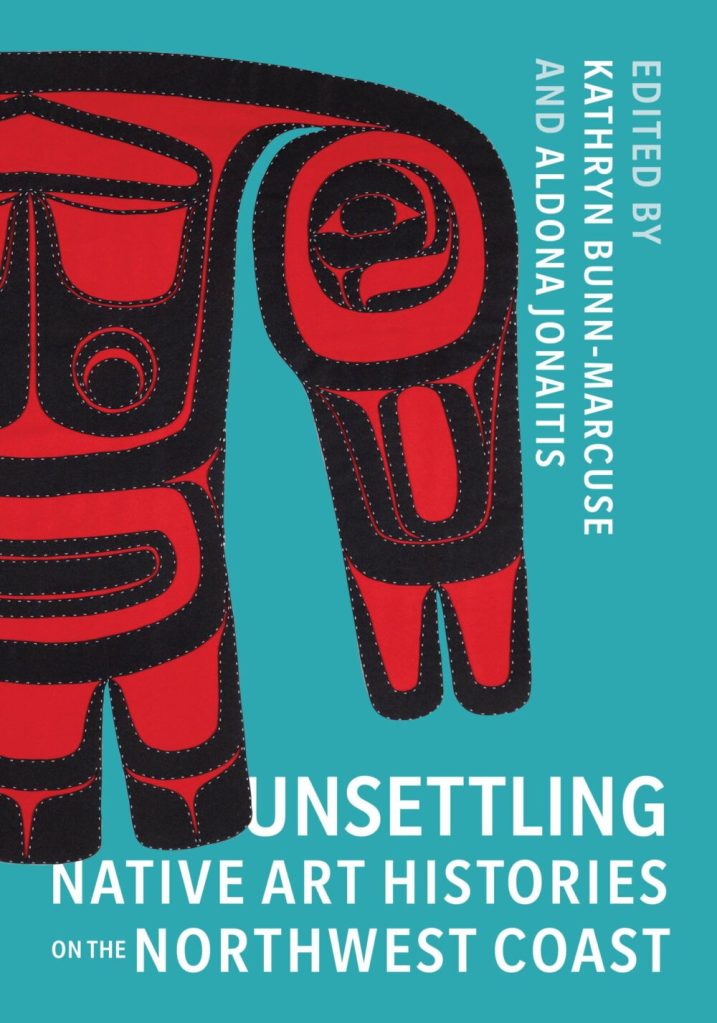

Decolonizing Northwest Coast art: Book Review

I just reviewed this book for the Ormsby Review. It is a wonderful book and I highly recommend it. Doing a review forces you to really think about what you are reading and this book still has me thinking it over. There is so much to learn by reading it. I could go on and on, but that would be silly since I already did that. You can read the full review here: Unsettling Native Art Histories on the Northwest Coast and if you are looking to purchase it, please support your local bookstore or you can purchase it from the publisher, the University of Washington

Telling Tales: Twist as storyteller (In Press: Spin Off Summer 2021)

Links to further resources for the article:

Khipus:

For more information about Manuel Medrano, the student working on the khipus code: There is also Gary Urton’s khipu online resource And Sabine Hyland’s web site where she shares resources about studying the Inka narrative khipu texts.

Jane Wheeler has done amazing research into ancient llamas and alpacas.

For more on Icelandic and Viking textiles, Michele Hayeur Smith has done extensive textile studies on Northern textiles (Iceland, Greenland, Faroe Islands). Her new book The Valkyries’ Loom: The archaeology of cloth production and female power in the North Atlantic was released in November 2020.

The Coast Salish Woolly Dog (Ply Magazine Spring 2020)

Spinning dog hair may seem a bizarre notion, something only a besotted dog owner or an obsessive experimental spinner would consider. But according to oral history of the Coast Salish people of the Pacific Northwest, they not only spun dog “wool,” they raised a breed of dog to ensure a supply of dog wool for their blankets.From First Nations accounts, we learn of these woolly dogs living in Coast Salish territory, mostly around Vancouver, BC; Olympia and the Olympic Peninsula in Washington State; and on the southern coast of Vancouver Island.

Until a dozen or so years ago, the Coast Salish woolly dogs were something of a mystery. What did they look like? Did a separate breed really exist? If so, was the breed specifically kept for their fibre to spin into yarn? And whatever happened to them?

The River Runs Red – The sockeye salmon of the Adams River (Bill Pennell, Mark Kaarremaa, Tim Goater, Liz Hammond-Kaarremaa 2020)

The River Runs Red weaves the biology of Adams River sockeye salmon with over 100 magnificent photographs. It is a story showcasing one of nature’s great wonders, the epic migrations of sockeye on a four-year cycle from the egg to the ultimate deaths of the returning adults on the spawning grounds of the Adams River in British Columbia. Significant historical, cultural and ecological perspectives surrounding this iconic fish species are presented. This story is captured by four friends: two biologists, one photographer and one creative organizer all of whom for over twenty years, returned to the river every four years for the ‘big’ run.

Coast Salish Robes of Wealth in Selvedge: The Fabric of your Life (October 2019)

I am in Seattle, the far northwest of USA. We watch as a group of local Suquamish Coast Salish weavers and singers are surrounding a plain-woven blanket displayed on a table in front of an audience, singing to it as if it was alive, blessing and welcoming it out of the back-storage room of the Burke Museum. There was electricity in the air: we all felt the singular veneration for this blanket.

Book Review: Honouring Salish blankets (The Ormsby Review #442 December 2018) Coast Salish Robes of Wealth

Imagine a blanket spread out on a table. It is a Salish blanket, over a hundred years old, humble, plain, tan-coloured, with a dark brown stripe at each end. Worn and frayed, it does not look exceptional, yet a group of six women and men surround it in reverence. They are Suquamish (Puget Sound Salish) First Nation singers and weavers. They are singing an honour song to welcome the blanket back – back from the obscurity of a storeroom of the Burke Museum in Seattle. The sight and sound sends chills up the spines of the people watching, a large gathering of some 100 people. One weaver gently places her hands lovingly on the blanket. They are shaking with emotion. Another woman gives a prayer of thanks to the blanket…

Warm west coast wool: Salish style in Ply Magazine Blog (January 2021)

Cowichan sweaters are famous throughout the world for being thick, light, warm and cosy. The yarns demonstrate ancient expertise with spinning warm yarns. The Cowichan (now known as Quw’utsun) First Nations of Vancouver Island on the west coast of Canada, are part of the Coast Salish language family of nations surrounding the Salish Sea and Puget Sound. They, along with their neighbours have been spinning warm yarns for thousands of years, yet sheep only arrived in the area in the mid-1850’s. So how did they learn to spin such warm fibres in a land where animal fibres are rare? And what can they teach us about spinning warm yarns?

A Curious Clay: The Use of a Powdered White Substance in Coast Salish Spinning and Woven Blankets in BC Studies Spring 2016

Early explore and settler accounts mention a white clay-like powder used in preparing Mountain Goat and Salish Woolly dog fibres for spinning. This paper looks at these accounts to try to clarify what the clay-like powder is, why it was used and where it comes from.

Coast Salish Spinning: Looking for twist finding change in in Textile Society of America Proceedings 2014

Coast Salish textiles from the Pacific Northwest (northwest Washington state and southwest British Columbia) are relatively rare and unknown yet are masterpieces of sophisticated weaving and spinning techniques. Coast Salish blankets and robes, and the tools used to make them, have been the subjects of a few seminal works, but other than the occasional recording of the direction of twist, the spinning characteristics of the yarn itself have not been the focus of research. This gap is curious, given the uniqueness of Coast Salish spinning tools, the corresponding techniques, and the fibres used. Notable examples are the Salish large spindle, which employs a tossing motion and was used with mountain goat and dog wool, and the Indian Head spinner, used to produce Cowichan sweater yarn from local sheep’s wool. …

Threads, twist and fibre: Looking at Coast Salish Textiles in Textile Society of America Proceedings 2018

Coast Salish textiles are: remarkable for their quality; unusual in the fibres used; notable in their designs; singular in the innovative processes used to manufacture them. Salish textiles were determined by geography, shaped by trade, and influenced by colonization. That the textile tradition has survived is a reflection of the prestige they hold and the importance of the textiles in the Coast Salish culture. Relatively unknown and underappreciated, the older textiles deserve to be looked at with fresh eyes and modern methods that bring to light the outstanding abilities of the Coast Salish women in the creation of these important textiles. …

To Catch a Hummingbird in Beautiful British Columbia Spring 1997

My first thought upon reading the workshop description on banding rufous hummingbirds is “How the heck does one capture a Hummingbird?” My second question, following quickly on the heels of the first, is “How big are the bands?” And then, with incredulity, “How big is the lettering on the bands?”